Orbán threatens to veto next EU budget, and talks about a post-2026 problem, but Hungary could lose billions of euros within weeks

In an interview with the public radio last Friday, Viktor Orbán threatened to veto the EU budget over Hungary's frozen funds, and said that making the remaining frozen funds available would be a post-2026 problem.

The problem with this tactic is that a decision on the seven-year budget is not expected for a long time, while deadlines that could mean the loss of huge amounts of funding are about to expire. Hungary stands to lose more than 400 billion forints within weeks, and even the theoretical chance of avoiding this is close to zero – and on top of it, this is nowhere near the size of the stakes for 2026. What Hungary's EU Affairs Minister said a few days prior to the PM’s radio interview had actually set the scene for the Prime Minister's veto threat, and Orbán's current approach is also apparent from his handling of the 'Erasmus issue'.

A faulty assessment of the situation to begin with

"As far as the funds are concerned, I am amazed to see that Hungarian public debates tend to be characterised by people speaking with complete confidence about facts they have no knowledge of. This is clearly evident because they are talking nonsense," the Prime Minister began his assessment of the situation on Friday, only to shortly afterwards follow it up with a statement that had been essentially refuted by the government itself a few days before. "The EUR 12 billion are there in Hungary's account. This money is at our disposal, we can bring it into the Hungarian economy", he said, using largely the same argument as in September.

Simply put, there are three main channels through which EU money distributed through the government can come into Hungary:

- from the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP);

- the recovery fund;

- and the catch-up funds.

Given the size of the sum mentioned and the method of drawing it down discussed later in the conversation, both in September and last Friday Orbán was only talking about the last of these, the catch-up funds. Indeed, this roughly €22 billion was previously set aside for Hungary in the EU's current seven-year budget, which runs until 2027 – in fact, the money can be drawn down for an additional two years.

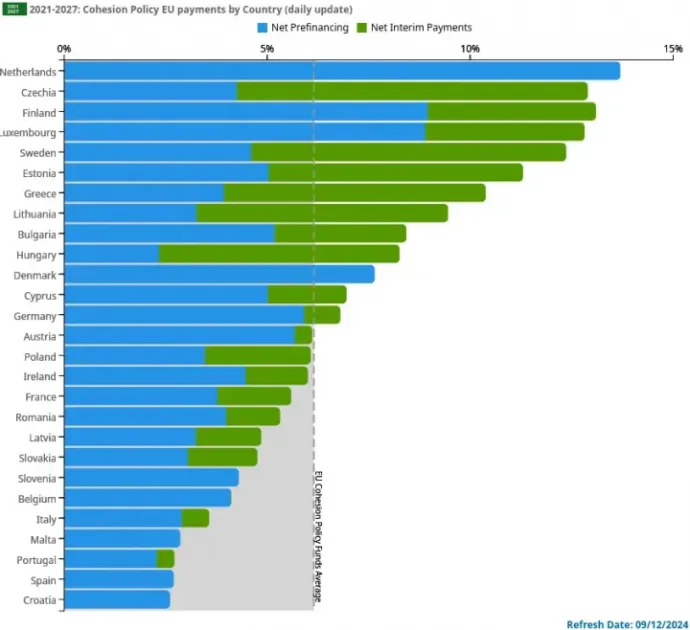

The Prime Minister more or less even outlined the process whereby the transfers always end up coming in at the end: first the government announces the tenders, the winners are then paid from the state budget, and only after their implementation can the government present the invoices to the European Commission, which then reimburses the amount following an audit. Given that tenders are announced progressively, and the EC doesn't pay out the funds until the very end, the payment curve typically starts out flat and then gradually climbs up as the seven-year period nears its end. At this point, we are only around the halfway point of the cycle which started in 2021, and relative to the other Member States, Hungary is well positioned. Although the Prime Minister spoke of seventh place in September, we have since slipped back to the tenth as of 9 December.

The judicial reform package the government managed to have the European Commission agree to last December used to block the funds almost entirely. Some of the money is still not available due to further rule of law and technical conditions. Of the latter, in March this year, the government managed to fulfill the requirements for having the more than €12 billion (as mentioned by the PM) made available. According to the summary of the European Commission, we are currently at around 1.8 billion on this, meaning that there are still more than ten billions' worth of bills to be shovelled in, so if this is all one looks at, then the Prime Minister outlined the situation quite correctly.

The problem begins with his claim that this money is available now. It was in response to a question from Index several days ago that the Ministry of Public Administration and Regional Development itself said that not a penny had arrived from this fund since the end of June, almost six months ago. Although the author did not elaborate on the reason, and tried to justify the situation with the summer vacations, that argument is much less believable in December than it would have been at the time of Orbán's September comment.

The real reason may rather be the fine that the ECJ had imposed on Hungary for not complying with EU asylum laws in June. The fine, which has increased by one million euros with each day that has passed since then, along with the 200 million euro penalty, stands at roughly 380 million euros as of 9 December. All of this may be deducted from EU subsidies, which the European Commission usually initiates every two to three months. However, a source in the body told EUrologus in mid-November that there are simply not enough invoices yet to deduct the full amount.

If this is the case, it would mean that the cash that the government requested between the imposition of the fine and its most recent collection from this fund has been completely dried up for the time being.

This does not mean that the European Commission will reclaim the tender funds already allocated from the Hungarian budget, so those who received them do not need to worry: it is as if the state had subsidised them – except that the money will not flow back into the Hungarian budget later on. The funds can, in principle, be deducted from any subsidies, including agricultural ones. The government is supposedly negotiating with the "intention of reaching an agreement", but has so far only managed to come up with a timetable and the methodology.

Orbán seems to have forgotten about a few billion euros

The most interesting remarks about these very terms came from Orbán after his assessment of the situation. “As for the EUR 12.5 billion, it should be known that it will meet the needs of the Hungarian economy until the end of 2026. There will be more funds for us beyond that, and whether or not it will be there will be a problem for after 2026.”

If the catch-up funding were the only issue on the table, the Prime Minister's point might even be understandable: the government probably expects that the €22 billion in catch-up funding would hit the current ceiling of more than €12 billion around that time.

One major problem is that Orbán is simply acting as if the third "tap" (outside of the agricultural and the catch-up funding), i.e. the recovery funding, did not exist, and this is not at all a post-2026 problem. The state can claim 10.4 billion euros from the one-off fund, partly as non-repayable grants and partly as soft loans.

In an interview published on Válasz Online on Monday, Tibor Navracsics said that "we were able to agree on the money for the reconstruction fund by December 2023". This agreement was only about the part of the loan that the government had previously referred to as the Soros plan, but later ended up requesting, and the supplement to the original spending plan, which via a circumvention of sorts only opened the way for an advance of almost one billion euros. It was received in two instalments by February, but the government is still not in a position to submit a regular request for disbursement.

The problem is that

while Orbán said that this would be a problem after the end of 2026, the remaining amount can only be called down until August 2026, after which it will be gone for good. After the advance pamyents that have already been made are deducted, that leaves nearly €6.4 billion in non-repayable subsidies and more than €3.1 billion in loans.

Moreover, the government has already included 630 billion forints from here in next year's budget, although the Fiscal Council has identified this item as a "significant risk".

For Hungary to be able to submit payment requests at all, 27 super-milestones would have to be met (after which there are still more than a hundred ordinary milestones, although the government is making some progress on some of these, such as the utilisation of wind power and the raising of teachers' salaries, among others.) With the justice reform package, the government ticked off four super-milestones.

We stand to lose more than 400 billion forints within weeks

Based on the above, the government could have a little more than a year. But there is an even more pressing problem: the conditionality mechanism. Here, the expectations are now almost fully in line with the super-milestones (21 out of 23). This is the biggest chunk of the still blocked part of the catch-up funds. It is keeping roughly €6.3 billion blocked, and in addition to this, "commitments suspended in year n cannot be included in the budget after year n+2". The procedure was decided almost unanimously by national governments in December 2022, and it means that

at the end of this year, Hungary will lose more than €1 billion.

Even EU Affairs Minister János Bóka admitted this earlier when he said: if the suspension is maintained in the long term, we could lose funds, which could happen as early as the end of this year, but “we are working to ensure that this is not the case”.

The number of conditions the government has fulfilled is not publicly available. Last December, when the judicial reform package was accepted, the European Commission issued an informal evaluation, but all it said was that not all the expectations had been met.

Prior to our summary last May, a source with insight into the matter said that "lots of things have been ticked off". At the end of November, Transparency International's analysis came to the conclusion that according to them, a significant number of the conditions had not been met or had only been partially met. Of course, the European Commission and the Council may be much more soft-hearted though, but there will not be much room for manoeuvre when it comes to measurable targets with deadlines. For example, according to TI, the application of a new system of sanctions for serious breaches of asset declaration obligations was not introduced by the third quarter of last year and the proportion of single tender public procurement contracts was not sufficiently reduced by the set deadline.

However, government officials have regularly said that they believe they have complied with all requirements. If they truly believed so, they could ask for a re-evaluation of the conditions. Indeed, at the beginning of December, the government did so for the conditionality mechanism, but what it did and how it went about it is indicative of its current attitude.

The handling of the 'Erasmus case' had already demonstrated the government's marked reluctance to deliver

One specific part of the conditionality mechanism would have needed to be dealt with so urgently that by now, the government has already missed several deadlines. As well as part of the catch-up funding being frozen, 'public trust foundations' and institutions (mostly universities) maintained by them (our earlier article discusses this in detail) have been banned from all EU commitments, meaning they are effectively unable to apply for any new EU tenders. Not only is this the case with the Cohesion Funding, but with any programmes, even those not managed through the Hungarian government, but more directly by the European Commission.

Some of these public trust foundations operate one of the twenty-one universities which underwent a model change, while others, such as the MOL-Új Európa Alapítvány (MOL-New Europe Foundation) which has recently been in the news due to its spending plans and lack of transparency, and which is behind Mathias Corvinus Collegium or MCC) do not. Member states agreed with the commission's view that the operation of these public trust foundations is not transparent enough, and that having political decision-makers on their boards is incompatible with their function. So far, the Hungarian government has failed to address the commission's objections, which were made known months before December 2022.

The measure has been progressively causing more and more problems for the universities which underwent the model change. By last summer, such institutions complained that the ban was costing them millions of euros in losses on Horizon Europe research collaborations, and by now their students are not even allowed to go on Erasmus exchanges.

Last autumn, both Szabad Európa and Telex received similar information, according to which an agreement on this and even on the whole conditionality procedure seemed close, but then something went very awry. We have heard conflicting readings from both sides on exactly what this was, but information from both the government and the European Commission concurs that they felt that the other side lacked the political will for an agreement. In January, Regional Development Minister Tibor Navracsics said that the negotiations had stalled.

The June EP elections could have provided another reason to hurry, given that the new European Commission goes on autopilot for a while after that. The new body took office on 1 December, and the very next day the Hungarian government requested an evaluation of the amendment on the public trust foundations, which the Hungarian Parliament had in the meantime adopted.

When it was published, the legislation was described by many as a capitulation, although it admittedly only reflected the government's own position and not all of the committee's proposals were accepted, as we also reported at the time. According to leaked information, it is weaker than the board expected it to be, and exempts foundations that are not behind an "institution of higher education using EU funds" from the majority of the restrictions.

"It's not really what we were hoping for," the new European Commission budget commissioner said, signalling that the government had already been warned about this. Piotr Serafin also clarified that the request only concerned the modifications pertaining to the public trust foundations, but not the catch-up funding (i.e. the conditions that are likely to cause a loss of more than €1 billion in funding at the end of the year). Given the one-month deadline for evaluation and the fact that the EU institutions are also going on holiday at the end of December, the chances of losing the money are now mostly mathematical.

The Commission will either pass the amendment on to national governments for a decision, indicating whether the conditions have been met in full or in part, or, if it sees no progress, it will inform the member state concerned and the others accordingly. In other words, despite knowing that it does not meet the Commission's expectations, compared to the current situation, the government does not stand to lose anything with the re-evaluation. In the best case scenario, it can rely on the goodwill of the ministers to give a partial approval, and in the worst case, if the amendment is rejected, it can blame the EU body for ruining things for Hungarian students – even though the amendment itself clearly is not concerned with their interests alone: part of it is actually not trying to exempt the model-changing universities' foundations from the restrictions.

The change in the government's attitude is shown by the fact that in May Bóka said that formally, the government could initiate a reassessment at any time, but in practice, at the request of the European Commission, this would have to be agreed in advance, and they intend to stick to this in good faith.

Here come the "political tools"

A few days before Orbán's comments on the radio, Bóka had already said that the rule of law conditions expected of the Hungarian government could no longer be interpreted as a legal and technical problem in their own right, but only as a political one. He considered them political instruments, so

although "we do not feel absolved" to cooperate with the EU institutions "as constructively as possible", they must be fought politically.

Shortly afterwards, the minister moved on the subject of the next seven-year budget, which he pointed out would require unanimity and then added that they would be aiming to "repair the damage".

Instead of subtle mentions of unanimity and talking about reparations, on Friday, Orbán was more specific about what the government was thinking. In his opinion, we will "of course get the money" , and more than what is available right now, because "negotiations have started on the budget for the seven year period after 2027, and accepting it requires unanimity".

"What I can say for sure" is that we will have to get the money "that we didn't get in '25-'26 in '27-'28, otherwise there will be no budget. I'm not going to give my consent."

It is not clear from his mention of 2027 and 2028 exactly what he is after: whether he would like Hungary to be given the amount it didn't get from the current budget in the new budget starting in 2028, or whether he would like all restrictions to be lifted by the end of the current cycle in 2027 in exchange for his consent for the next seven-year budget.

The latter could pose legal problems. The European Parliament (EP) is already suing the European Commission for approving the justice reform package last December, which previously blocked almost all the catch-up funding. The decision about this was made just a day before the last meeting of heads of state and government for the year, where they agreed on EU membership negotiations and further support for Ukraine, as well as on increasing the long-term EU budget.

In a January resolution, the EP stated that Viktor Orbán had already abused a veto on this occasion: "He was blocking the decision (which has since been passed) on the fundamental review of the Multiannual Financial Framework, including the aid package for Ukraine, in total disregard and violation of the EU's strategic interests”. According to the body, "such actions violate" the principle of loyal cooperation enshrined in the EU's quasi-constitution, the founding treaties. The Prime Minister himself had previously admitted that linking the mid-term review of the EU budget to the freezing of Hungarian subsidies would make him walk "on the edge of legality". But before that, when asked about the availability of the funds in Tusványos last summer, he said that a budget increase "requires unanimity. And then you have to hold the bag and that's it. That's how it is. Like this. And that's the plan."

The other option is to simply have an amount equal to what has been lost added to the amount set aside for Hungary in the new budget. The question is how receptive the EP and the other countries' leaders would be to this, especially the net contributors (and especially in light of the fact that the Hungarian government admittedly did not comply with all of the Commission's requests, for example, in the case of the public trust foundations operating universities). Moreover, the recovery fund is a one-off instrument on top of the budget, which will expire in 2026, which means that funds equaling a few thousand billion forints would have to be thrown in from the regular budget.

It could be a while before money comes

In the meantime, the Hungarian budget would have to cover the deficit for the developments that have already been paid for, and the rest would have to be either covered from national resources or halted. All this at a time when there's a significant deficit in the budget, which also resulted in an excessive deficit procedure being launched against the country. Additionally, one of the three major credit rating agencies, Moody's, recently downgraded Hungary in part precisely because "the country could end up losing a significant part of its planned EU funding if it fails to meet the conditions for the release of the same". Once the downgrading begins, financing the country's debt could become more difficult and more expensive, which would worsen the overall situation of the state budget. Failing to bring in the recovery funds before the 2026 election wouldn’t benefit the government politically either, as there would be that much less available to be handed out, while the current polls are looking quite close (between the governing Fidesz-KDNP coalition and their main challenger, the Tisza Party).

No proposal has even been made for the next seven-year budget of the EU. At the current stage, member states are issuing declarations of principle (which have no legal consequences) on policies, such as the one recently issued – under the Hungarian presidency – on the common agricultural policy. At his recent parliamentary hearing, Bóka said that he expects the proposal for the second half of 2025, and other sources have also suggested a date around next summer.

Decisions are usually dragged out until the last minute: the current 2021-2027 framework was agreed by heads of state and government in July 2020, but member states only reached a final deal with the European Parliament in November of that year.

However, contrary to Orbán's words, there would be an EU budget even if a member state were to veto it: in that case, they would continue with the current figures. Moreover, the conditionality procedure could be restarted at any time and the European Commission could apply the same horizontal conditionality it used before to block catch-up funding until the justice reforms were implemented. In addition, there is talk within the body both openly and, according to Szabad Európa, behind-the-scenes, about strengthening the instruments, and according to Népszava's sources, a system of fund distribution which would bypass governments in the event of freezing funds is also being worked on.

Meanwhile, there have been indications that the Hungarian government is moving ahead with the conditions, and the veto threat is just a back-up plan. As Portfolio has spotted, on Tuesday, the government made an amendment pertaining to the recovery fund available for public consultation which could contribute to complying with the super-milestones.

For more quick, accurate and impartial news from and about Hungary, subscribe to the Telex English newsletter!