The Orbán-Trump relationship: a black box we will soon get to peer into

"Antal Rogán's position in Hungarian politics and in the Hungarian government has been strengthened as never before. All I can gather from this is that he is doing his job well" – this is how Viktor Orbán evaluated Washington's sanctioning of one of his most important ministers in a radio interview. The head of the Hungarian government spoke about this just a few days before Donald Trump took the US presidency over from Joe Biden.

In the face of outside attacks, Orbán has been known to defend his people rather than replace them. This was also the case with Balázs Orbán, the PM’s political advisor, whose statement about the 1956 Hungarian revolution was seen as a mistake by the Prime Minister too, but who was left in his position nonetheless. Admittedly, as the Trump administration is currently being set up, this could be the time for him to prove his importance, given that he has had a role in Fidesz's relation-building efforts in the US for several years.

Although the opposition did not seriously address Rogán's case, and even many of the system's critics considered it a belated, and in some cases politically counterproductive move, having one of the most powerful members of the government on the US blacklist certainly has national security and diplomatic implications. It will therefore matter a great deal how the new administration in Washington is going to deal with the issue, as well as how quickly it will put an end to it.

As long as Rogán remains on the list, countries with leaders who disagree with Orbán's policy on Russia, and even consider it dangerous, may become even more emboldened. From those in the region, this is especially true of Romania and Poland.

These states may even interpret the US sanctions as permission to fire on the Hungarian political leadership. There have already been tangible signs of this, with some information at the recent meeting of the Parliament's National Security Committee suggesting that some actors in the region are interested in obstructing the rapprochement between Trump and Orbán, and are using intelligence tools to that end. If this is true, and not merely the product of some kind of paranoia, it could present a serious challenge to the government 14 months ahead of the parliamentary elections.

Those who have carefully followed the statements of Orbán's political director, Balázs Orbán, will have seen that the Hungarian government hopes that with Trump's arrival, there are new and better times ahead for them. This is because they believe that the new US administration will simply accept Hungary's particularist politics, namely, that the Orbán government wants to maintain an equal distance from the great powers, both when it comes to its relations with Russia or China.

The chaos of “a changing world order”

This was explained by Orbán's political director in an interview with Bloomberg, where he said that Trump's 'America First' mentality is something that European countries could adopt without incurring Washington's wrath. It's worth noting, however, that the slogan 'America first' can actually be a source of confusion for the European far right, which defines itself as patriotic. For example, the president of the Fidesz ally Austrian Freedom Party (FPÖ) was invited to Trump's inauguration, but refused to go because he did not like Trump's slogan of 'America first'. "Donald Trump says America first. And I say that Austria is first," said Herbert Kickl, whose words highlight how difficult it is to bring together those who in principle have the same opinion on sovereignty and patriotism. Of course, this makes perfect sense, since America can only be first to the detriment of others.

Orbán and his team are not bothered by these contradictions. They trust that the disintegration of the current world order will present the United States with a new situation, and that in a multipolar system America will be much more tolerant of countries seeking more flexible partnerships in their own interests. Many believe that the United States is no longer in a position to set the global agenda unilaterally or to expect other countries to follow it without asking questions.

One thing that Orbán and Trump have in common is that, to varying degrees, they have both contributed to the fragmentation of the global order, which for the time being is pushing the world towards a chaos full of question marks. In the first Trump administration, this manifested itself in taboo-breaking steps such as withdrawing from multilateral agreements, undermining global institutions and overhauling the framework for international trade and development.

Traditionally, it's been the US-led multilateral institutions – the IMF, the World Bank and the World Trade Organisation – that have been providing the foundations of the global order, promoting stability, open markets and development subsidies. But Trump's 'America First' policy has marked a sharp departure from this tradition, putting national sovereignty ahead of collective commitments.

Even if it is to be assumed that the upended order has birthed a new America, it is not at all certain that the hoped-for American leniency will primarily be exercised within the Western alliance system and not towards states such as India, Saudi Arabia or the United Arab Emirates. It is also a bold and naive idea that what is good for Trump's America is good for Hungary. One only has to consider the customs tariffs promised by Trump, which would primarily target the German economy, which Hungary is tied to.

Neither is the fact that Trump would expect NATO member states to contribute more money to the military defence alliance a signal of a flexible partnership. Although the current Polish leadership is ideologically closer to the Biden administration and it would be daring to call them Trump supporters, Warsaw immediately indicated that it would be able to accommodate the new president's request on this. And how did the Hungarian Prime Minister, who is supposedly close to Trump, react to the same suggestion? He said that if Hungary were to increase its military spending, the Hungarian economy would shoot itself in the foot. The reaction may sound familiar, because Orbán feels the same way about the sanctions against Russia, with which he believes the EU has shot itself in the foot.

Beyond friendship

Although personal relationships and ideological connections can and do play an important role in international relations and diplomacy, they are never the fundamental determining factors of actual decision-making – especially when America puts its own self-interest first. We have seen it happen before that the Hungarian government considered a foreign actor taking a post very promising and believed that this could significantly improve Hungary's position, only to have their calculations fail.

Germany's Ursula von der Leyen, for example, was elected to head the EU's quasi-government in 2019 with the support of Viktor Orbán, among others, but just a few years later, both the Hungarian press controlled by the governing party and Fidesz politicians were talking about her in a similar tone as they do about George Soros.

Viktor Orbán and Italy's Giorgia Meloni used to have a good relationship, much like what we are now seeing with Trump. The Hungarian Prime Minister had hoped for Meloni's victory and had counted on an alliance with her, but ended up not getting what he had hoped for. So it is also possible that, like Meloni, Trump will turn his back on Orbán on certain issues. For example, because both his business interests and US interests dictate that he should build a better relationship with Eastern European states that, unlike Orbán, want to build a strong alliance with the US administration regardless of who is president. If that happens, Poland and Romania will be the only ones to emerge as winners. Additionally, countries for which seeking compromise and adjusting is more important than a stand-alone, confrontation-based policy or pushing for their own petty interests are generally in an easier position, if only because of their flexibility.

What is apparent is that Hungarian interests – for who knows what reason – have for quite some time been aligned with Russian foreign policy strategy, which also explains the lack of flexibility.

The inflexibility of Orbán's foreign policy could therefore backfire even under a Trump administration. It remains to be seen whether it will.

In any case, the Orbán government is hoping that the new US administration will be indifferent to the number of meetings or phone calls between Péter Szijjártó and the Russian foreign minister, the extent to which the pro-Fidesz media echoes the familiar Russian propaganda about the war in Ukraine, the steps the Hungarian government is taking to help pro-Russian Georgian political forces, or the extent to which it is opening Europe's doors to the Chinese – to name just a few of the things that the Democratic administration was upset about. We will find out soon enough. What could potentially be an ominous sign for an administration that is too close to the Russians is that under Trump, the CIA is expected to become much more aggressive and daring abroad, or at least that is what its future director, John Ratcliffe, intends to do.

Awaiting a golden age

What will become of the issues that the Hungarian and US diplomacy will have to sort through in addition to the Rogán story will also be seen in the season ahead. The Prime Minister mentioned back in December that the Hungarian government would like to reach an agreement with the new administration on the double taxation ban, the visa waiver and on US capital investment.

Many believe that America leaving them alone would be enough for Orbán, which is their minimal political goal. But the fact that Orbán sees Trump as a sort of messiah has led to high expectations. In a radio interview last Friday, the Prime Minister said that Trump would usher in a "fantastic, great golden age" in US-Hungarian relations, which Hungarians would also notice in their finances. He is clearly hoping for billions in US capital investment, and he himself does not believe that Trump will put an end to the Russian-Ukrainian war in the foreseeable future. Trump's team does not believe that either.

"As of Tuesday, a different sun will rise over the Western world," Orbán said in his radio interview last week. This is not the first time he has suggested that everything would change with Trump's arrival. He made the same point at the Széll Kálmán Foundation's Christmas dinner at the end of last year, when he noted that Hungary would soon be granting political asylum to a Polish citizen, thereby completely wrecking the already crumbling Polish-Hungarian relations.

A black box

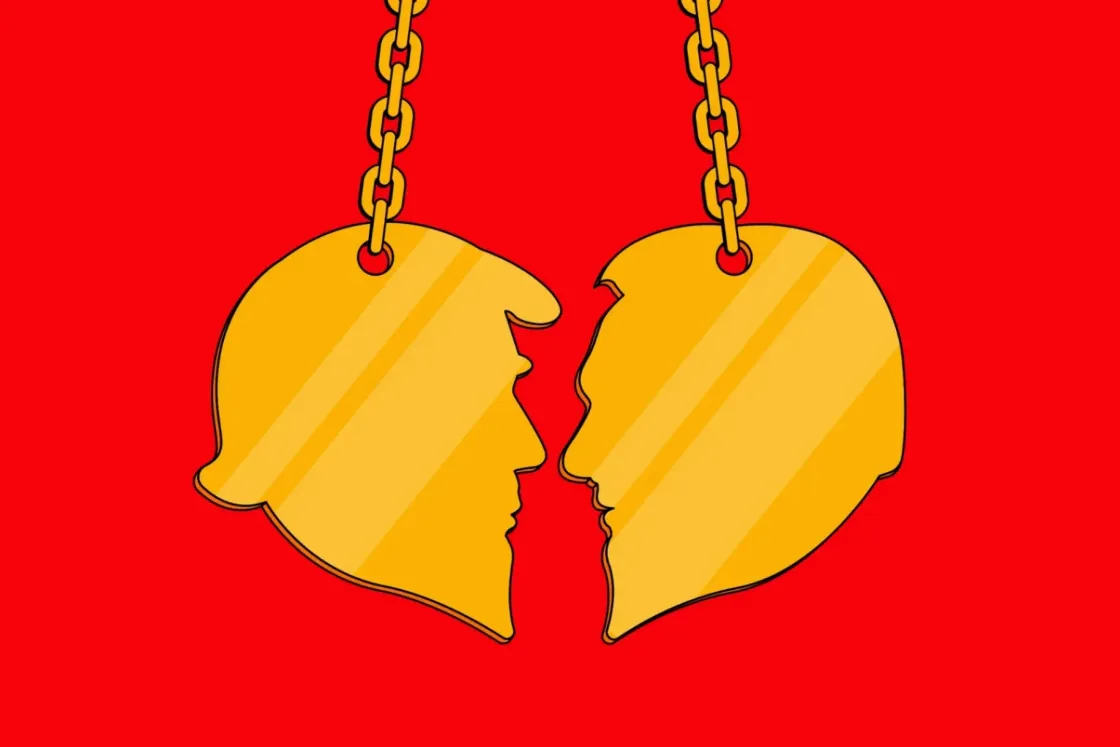

The relationship between Orbán and Trump is portrayed in two ways in the domestic public arena.

The ruling party has tried to portray the relationship between the two leaders as a deep, almost friendly, but certainly allied relationship, ascribing an almost messianic role to the new US president. Others believe that the quality of the relationships that certain Fidesz actors have been systematically working to build with US conservative circles for years is simply misinterpreted, or at least overrated.

However, no one would dare bet on either narrative, given Trump's unpredictability, because no one knows exactly what is coming.

It is no wonder that the mystified relationship between Orbán and Trump, the details of which are less known has analysts scrambling to grasp every little detail, hoping to glean something from the most subtle signs and gestures. This is why some have tried to draw far-reaching conclusions from whether or not Orbán was invited to Trump's inauguration ceremony, and if not, why. At the same time, no one can say for sure whether this in fact has any significance in terms of the future.

Even if the future of the relationship cannot be judged, its history is well known. Unlike other European leaders, Orbán did not have to go turncoat after Trump's victory, which will certainly count much in the eyes of the new president, who is known for being vain, even though Hungary is not a major geopolitical and economic player from an American perspective.

Orbán was the first European politician to back Trump, even before anyone gave him serious consideration, and he has consistently backed him in the past few years. Even when it was embarrassing. The Hungarian Prime Minister has gone so far in his homage to Trump that he has been boldly proclaiming the blatant lie that the previous US presidential election was rigged.

He may be able to appeal to Trump's vanity with this kind of communication, and if he continues in this vein, he may soon be seen as a politician who is not only pro-Russian but also pro-American, but that really doesn't make much of a difference. Instead, the real question is how deeply Fidesz's network of US contacts is embedded in the new administration, and who Trump will listen to when making a decision. In other words: how close will the figures Orbán's people have been deepening their ties with in recent years be to the president?

Even more important is the extent to which Trump will listen to those who are taking a pro-Russian position on the Russia-Ukraine war. Or perhaps how much he will listen to those who say that the United States should strengthen its relationship with those who have proven their loyalty regardless of presidential terms. In the latter case, Orbán might end up with Trump like he did with Meloni or Ursula von der Leyen.

We will find out this year whether Orbán's strategy on America is working

As we previously reported, Trump's vice-president, 39-year-old Senator J.D. Vance, is one of Viktor Orbán's biggest fans overseas, and he is not afraid of making blatantly false claims when it comes to defending the Fidesz government's performance. In recent years, he has repeatedly campaigned in favour of the United States following Hungary's example, whether regarding the Orbán government's family policies or the "child protection" referendum or the "banning of LGBTQ propaganda" from Hungarian schools. Vance blamed the Democrats' rhetoric for the assassination attempt on Trump. When it comes to the Russia-Ukraine war, he is practically on the same page as Orbán, and opposes aiding Ukraine. It is another matter altogether that the Russia-Ukraine issue will not be his area of responsibility, so what he thinks on this is far from authoritative. But he was undoubtedly elevated to his position by the circle with the closest ideological ties to Fidesz.

Szabad Európa has previously explored the US relationships of Hungarian government circles in relative detail. The paper's series of articles reveals that the Orbán government has forged relatively good relations with the Trumpist wing of the Republican Party and with various Trumpist think-tanks, which may be to their advantage because by now Trump has moulded the party in his own image. This relationship building cost the Hungarian taxpayers a lot of money, but it is far from certain that it was a worthwhile investment.

In addition to the fact that there is no unanimity on the American right about Orbán, and that there are Republicans who see the Hungarian leader as a national security risk, it is also important to note that the alliance which has developed between the Trumpists and Hungarian government circles is more about ideological issues. These include family policy, the issue of gender, and an anti-LGBTQ sentiment.

Although these ideological ties may in the longer term underpin Russian geopolitical aspirations, if Trump's policy towards Russia is not calibrated according to Orbán's and Moscow's understanding of "peace policy", their impact on the war will be less noticeable.

The fact that the Trumpist wing is not homogeneous, and that conflicts of interest have become evident even before actually taking power (for example between Steve Bannon and the tech moguls) may also prove to be risky for Orbán. Additionally, the new president himself is known more for his unpredictability than for his firm convictions. Moreover, whatever the relationship of some government officials with the future Trump administration or the think-tanks hovering around them, other Central and Eastern European countries will also be looking for the US president's favour. This could prove significant because the Republicans that the Orbán team has courted in recent years are not well versed in national security issues.

The good news is that the moment of truth will certainly come in 2025. If in the foreseeable future, i.e. within weeks or months, there is no progress on the American issues that are important for Hungary, then what we have been seeing and hearing about Orbán's theories regarding the shift to a new world order has been nothing more than window dressing and political bullshit, a mere covering up of the fact that Fidesz's America strategy, which has cost a significant amount of public funds, is ultimately a failure, or at least not as successful as Orbán would have it appear.

Orbán worked on it for years, Meloni brought it home in a flash

Finally, it is worth returning to Meloni for a moment. Given Hungary's geographical and other characteristics, it was unlikely even before that Orbán would be Trump's most important European ally, even though the Hungarian Prime Minister was the first to visit the United States after the Republican presidential candidate's election victory.

After Trump's victory, however, there were reports according to which Orbán was hoping to reduce his isolation within Europe by serving as a mediator between Washington and Europe, with Putin's tacit support.

As Reuters noted after Trump's victory, this would be in line with Orbán seeing himself as a "peacemaker". This role already provoked a backlash from EU leaders last July, when Orbán visited Moscow and Kyiv without informing the EU or NATO in advance. Orbán concluded this "peace mission" at Trump's Florida estate, Mar-a-Lago, where he declared that “Trump will act as a peace broker as soon as he wins the election.”

As Reuters reported at the time, Brussels may be reluctant to let Orbán lead the negotiations on security or Ukraine. However, Trump's threat to impose a 10 percent tariff on all imports could encourage EU leaders to give Orbán a role as a mediator in trade talks, or at least that was the assessment at the time.

Except for the fact that Meloni, whom Trump also hosted at his Florida estate in January is considered a much bigger player than Orbán – and her standing in the EU is nothing like Orbán's. It should not be overlooked that Meloni represents the opposite of what Orbán does on the Russia-Ukraine issue. And it is also worth noting that, even if the EU might appear to be shifting towards the right, and public support for Ukraine is not as strong as it was in 2022-2023, there is still a greater consensus on defence policy between the right and the left, with the pro-Russian far right in the minority for the time being.

Meloni is openly pro-Ukraine and considers the opinion, long voiced by Orbán, that the war has been decided in Russia's favour a long time ago to be Russian propaganda.

Assuming that Trump or his advisers are not stupid and have the best interests of the United States at heart, the new president will want a strong European ally with real influence on the old continent and the ability to make deals. In that case, Meloni could be a much better ally for Trump than Orbán.

The former is adept at combining populism with pragmatism, is politically more flexible, and there seems to be very little threat to her stable position as head of government in Italy, and in the long term she could become a major player in European politics. None of this is true of Orbán. Although he has undeniably become a political brand on the international stage, he is a much more divisive political figure, and is facing economic difficulties at home that even his party, Fidesz believes could threaten their victory in 2026. Although it is a gross exaggeration to talk of a mood for a change of government, no one can deny that, despite the electoral autocracy and seemingly endless resources, Fidesz's position, including Orbán's, is not as stable as it was at the end of 2022.

Meloni overtook him round the bend. It might not make any difference, but unlike Orbán, the Italian politician went to Trump's inauguration ceremony, and didn't consider it a matter of prestige to be just one of the crowd. She could afford to do that.

It is also noticeable that Meloni is making the most of this. Some suggest that the reason why she resigned as president of the European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR) at the end of last year was because she wanted to devote most of her energies to building an alliance with Trump. If that is the case, it may not be good news for Orbán.

For more quick, accurate and impartial news from and about Hungary, subscribe to the Telex English newsletter!