€1.1 billion reward handed to pro-government Hungarian media may end up being too much for the EU

“The reader is not stupid—they’ll notice if the government wishes them Merry Christmas across four pages of a single issue.” This is how Csaba Lukács, director of Magyar Hang, highlighted the absurd way state advertising is distributed in the Hungarian media.

In recent years, multiple media outlets have scrutinized the Hungarian government’s media funding system, which distorts the market. The subject has now resurfaced as Magyar Hang and another complainant, who has requested anonymity, have submitted a formal complaint to the European Commission (EC). The complaint details how the Hungarian government has been violating EU competition law by disguising state subsidies as advertising.

The complaint argues that pro-government media outlets, which align with the government's narrative, have gained an unfair advantage through unlawful means. The scale of the alleged misconduct is illustrated by an accompanying economic analysis, which estimates that 441 billion forints (€1.1 billion) -including interest – of illegal state subsidies should be repaid to the state treasury.

This figure represents the cumulative damage caused by the government's media policy since 2015.

This conclusion is particularly striking because in 2024, the total amount spent by advertisers in the entire Hungarian media, i.e. radio, television, online and print media, was 384.4 billion forints. This means that, according to the complaint, between 2015 and 2023, the Hungarian government distorted the conditions in the Hungarian press by an amount greater than what was spent on advertising in the media in a whole year.

The economic analysis supporting the complaint was authored by Kai-Uwe Kühn, the former Chief Economist at the European Commission's Directorate-General for Competition. It is significant that the complaint is backed by an expert who has in the past had close insight into EU competition policy matters and that it will be investigated by his former colleagues. Kühn was part of a larger team of Hungarian and international experts, according to Lukács, and the case has already drawn international media attention. Kühn has been interviewed by the Financial Times, and the subject has been covered by Bloomberg and the Dutch public broadcaster, while the EC Directorate-General for Competition has also received questions from journalists about the case.

Lukács believes this heightened attention and pressure could influence how and when the Commission responds to the Hungarian complaint. He recalls that a similar complaint was submitted in 2019 by Mérték Media Monitor, Klubrádió, and former MEP Benedek Jávor. That complaint, however, has yet to receive a response from the EC.

“What’s key about the current submission,” Lukács explained, “is that it removes the issue from the political arena and focuses strictly on the distortion of the market and the restriction of free competition. That’s the core mandate of the Commission’s Directorate-General for Competition, which should make a decision easier.”

He added that the submission also considers similar practices under previous left-wing governments, while emphasising that since 2010, Fidesz has utilized the state’s advertising apparatus on a much larger scale.

According to Lukács, in 2019, the Commission may have believed Orbán’s government was manageable. But by now it has become clear that the Hungarian prime minister is not aligned with the EU. There’s also greater international interest towards the situation in Hungary.” He remains hopeful that these factors may prompt the EC to deal with the application promptly.

No such thing in a normal market

The basis of Kühn's analysis is that, under EU law, when it comes to advertising, a state actor must behave like a market actor. An advertisement is successful if it reaches as many people as possible, which is in principle, what a state advertiser should aim for as well. However, the economic analysis concludes that the Hungarian state does not follow this logic with its advertising, but distributes it as a reward to the newspapers, online sites and TV stations it favours instead. The analysis uses several examples to illustrate the same pattern: once a media outlet comes under pro-government ownership, its share of state advertising increases significantly compared to market-based advertising, and this disparity persists as long as the outlet remains politically aligned with the government.

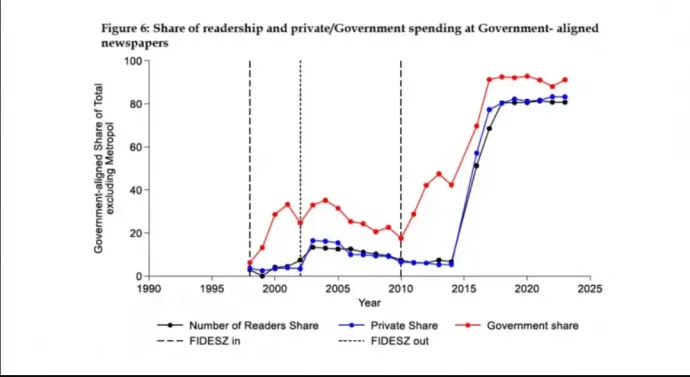

According to the analysis, commercial advertisers in Hungary have perfectly mirrored the steady decline in the readership of newspapers relevant from a public and economic perspective. The spending of advertising clients has fallen each year in line with the decline in readership of these newspapers. On the other hand, since the first Fidesz government came to power in 1998, newspapers which maintained a good relationship with those in power have had an unfair advantage, which was also the case under left-wing governments.

After Fidesz returned to power in 2010, however, the scale escalated dramatically. The proportion of state advertising began to spiral out of control, to the point where the Prime Minister's Office became the biggest advertiser on the Hungarian media market. With this, the Hungarian media was definitively split into two camps: pro-government outlets received substantial state advertising – this often being the income which sustained otherwise loss-making outlets – while critical or independent media received none, even when market logic would have justified otherwise, thus making it increasingly difficult for them to maintain their market position.

The analysis provides several examples from the print media, online media and the TV market, where the state has rewarded or even withdrawn state support as soon as the owner of a newspaper has fallen out of favour.

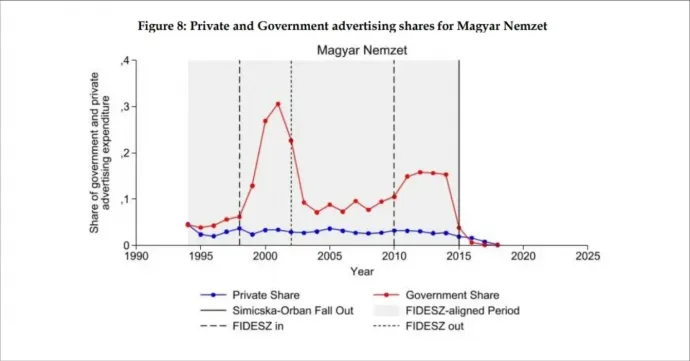

The case of the daily Magyar Nemzet is a good illustration of this. Under its previous owner, Lajos Simicska, the paper enjoyed high levels of state advertising during the first Fidesz government, while relations with party leadership remained cordial. When comparing Hungary’s 33 largest newspapers in 2001, the numbers show that Magyar Nemzet received 27 percent of total state advertising, compared to just 3.5 percent from advertisers from the market. But following a dramatic falling-out between Simicska and Viktor Orbán in 2015, the state abruptly cut advertising, dropping it below market levels. The paper soon ceased publication. (A new version of Magyar Nemzet was later relaunched under the name Magyar Idők in 2019.)

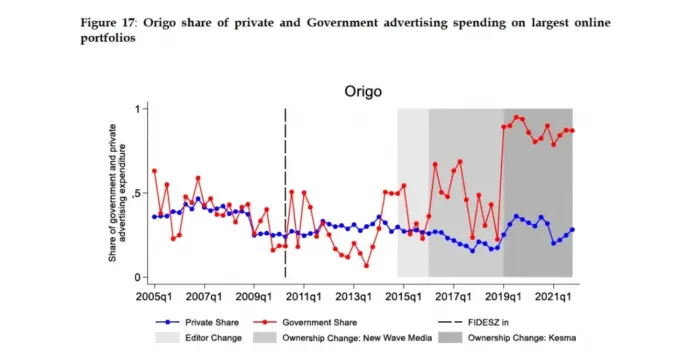

In the online media market, not all the relevant data were available for analysis, but the example of Origo shows the same technique. As long as [origo] was owned by Telekom and reported critically on the government's affairs, the level of state support did not even reach the level of advertising in the market (this is especially evident in the graph between 2011 and 2013).

Once the editor-in-chief, Gergő Sáling, was dismissed, and ownership was transferred from Telekom to the New Wave Media Group controlled by Ádám Matolcsy, public advertising surged. But the period from 2019 onwards is the most spectacular, as that was when Origo was merged into the government's central media conglomerate, KESMA (Central European Press and Media Foundation), which ushered in the era of state advertising abundance at Origo as well.

In the TV market, too, the fairness (or lack thereof) of the competition between the two dominant media companies, TV2 Group and RTL Hungary, one of which is state-backed, has been a topic of discussion for years. The analysis cites the year 2020 as an example: in that year, according to Kantar Media, the amount spent by the state on advertising on TV2 (HUF 23.7 billion) exceeded the total annual profit of RTL.

Kühn's citing of the RTL Group and Axel Springer – both of which are dominant players in the European media market – as examples, also points out that the government's market-distorting policy has also driven potential foreign investors away from the Hungarian media market, thus violating EU trade rules.

All obstacles have been removed

To facilitate this market-distorting intervention, the Hungarian government introduced a new system in 2015, after Lajos Simicska, Viktor Orbán’s ‘treasurer’, dramatically turned against him. Several new regulations were enacted to support this system, and a centralised media conglomerate, KESMA, was established. Nearly all pro-government media outlets were consolidated under its umbrella and then placed under the control of Mediaworks.

With Mediaworks overseeing all county newspapers, as well as Origo, Bors, and Hír TV, a media giant emerged that now dominates the entire Hungarian media landscape. The government designated this conglomerate as being of “national strategic importance,” effectively shielding it from any domestic competition law investigations. Further reducing transparency, Mediaworks has not disclosed details of its advertisers since 2022. According to the current complaint, dismantling KESMA would be essential to restoring Hungary’s media market.

The complaint submitted to the European Commission also clearly outlines the disguise employed by the government in issuing public tenders for government communications and by establishing the National Communications Office (Nemzeti Kommunikációs Hivatal -NKOH), led by Antal Rogán. This section is based, among other things, on the prior work of the Corruption Research Center Budapest (CRCB), which traced how two companies owned by Gyula Balásy (New Land Media and the Lounge Group), have ended up being the only "competitors" left standing when it comes to communication contracts with the state: According to Átlátszó's summary, Gyula Balásy's two companies, New Land Media and the Lounge Group, have in recent years been contracted by the state to the tune of HUF 293.7 billion.

In a separate section, the complaint reveals that the state has imposed conditions on these public procurement procedures since 2015 which ensure that as few domestic media agencies as possible comply with them.

Since the NKOH has each time based its conditions on the experience from the three prior years, the number of companies that remained in the running continued to decrease even more, so that by 2019, Balásy's consortium remained as the sole bidder and winner. In 2023, for example, Balásy's companies were the sole bidders in 80 public tenders announced by the NKOH, and they won all 80 of them.

The government argues that Balásy's companies are market players, selected in accordance with the law. However, according to the complaint submitted to the EC, the Hungarian government deliberately designed these public procurement procedures with a selective approach, and they have gradually become more and more like a single-player game. On top of that, the company in question doesn't even act like a market player, but functions more like a state agency that just carries out the tasks it's been given. In other words, these companies can work at above-market rates with no incentive to negotiate standard media discounts, contrary to industry norms.

What happens now?

The spokesperson for the European Commission said that the complaint is being processed. Oliver Bretz, from the law firm specializing in EU competition law, which represents the complainants, told the Financial Times that the situation clearly involves illegal state aid. He added that if the case concerned any sector other than the media, the Commission would likely have acted much more swiftly.

If the Commission eventually opens an inquiry into the matter, that in itself would send a strong signal, especially given that we are talking about the only member state which voted against the EU's Media Frredom Act, which – among others – requires companies to disclose how they use public funds obtained through state advertising and financial support.

For more quick, accurate and impartial news from and about Hungary, subscribe to the Telex English newsletter!