The world-class Hungarian swimmer whose love even the Iron Curtain couldn't stop

21 October 1950 was an important day in the history of Hungarian swimming. Since she had failed to break the world record three days earlier and had to settle for a national record, Éva Novák stepped onto the starting block at the swimming pool in Székesfehérvár with the intention to be the fastest in the world at that day's competition.

Novák was already an experienced competitor in the 200-meter breaststroke, having finished third at the 1948 Olympics when she was 18. She swam brilliantly in Székesfehérvár, her turns were good, she pushed hard, and finished in 2:48.8, which was four tenths of a second better than the existing world record held by Dutch swimmer Nel van Vliet.

She could not have known at the time that setting this world record would radically alter her entire life.

And not because she would become an even more celebrated star in Hungary after becoming the first female swimmer in the country to set a world record. Her record not only caused a huge stir in the Eastern Bloc, but in Western Europe as well. The Brussels-based Les Sports magazine reacted with a rather scathing article in November: "Do stopwatches work differently in Hungary, behind the Iron Curtain?" they asked disparagingly.

The article reached Novák, and since she spoke French, she promptly penned an angry letter to the editors questioning the basis for their doubts about her performance. To be on the safe side, she then set another world record on December 30, 1950, in a 25-meter pool in Ózd.

The Belgians responded. The first exchange of letters took place exactly seventy-five years ago, in January 1951. Pierre Gerard, the column's editor not only sent a letter but a formal invitation to a demonstration competition in Liège, Belgium. Although Hungarian competitors were not allowed to take part in the European Championships in Vienna in 1950 for political reasons, Novák was allowed to compete in this event. (Presumably not alone, but with her teammates.) It was there that she was able to meet Gerard in person.

"It was love at first sight" – Novák recalled the lightning bolt-like encounter in a later interview. Before she headed home, she told Gerard, who was twenty years her senior, to visit Hungary sometime.

Since the editor was also interested in the Hungarian competitor, he unexpectedly showed up on Margit Island one day, while István Hunyadfi was holding a training session for the Hungarian champion. At that time, the Belgian had to request the Hungarian authorities’ permission to enter the country, and only after it was granted could he set off. Gerard witnessed first-hand how hard the Hungarian athlete trained, but they also grew closer emotionally.

As it later turned out, they went to the theater, and Novák introduced her suitor to her family, which the authorities had no idea about yet, given that their love seemed so irrational given the political situation between the two countries. However, they firmly believed that even the Iron Curtain could not present an insurmountable obstacle.

Since Gerard's Hungarian visa was valid for a limited period of time, no matter how strong their love was, he had to return home. In May 1951 in Moscow, Novák once again broke the world record in the 200-meter breaststroke, but there were no major international competitions that year, only a year later.

Novák travelled to the 1952 Helsinki Olympics as a favourite, and Gerard was there to report on the event for his newspaper. The Hungarian secret police had gathered detailed information on everyone, especially the favorites, but according to research, Novák was not on the list of those under surveillance. The ÁVH (Hungary's notorious secret police between 1948-1956) was probably unaware of their romantic involvement and would never have imagined that they were planning to get married at the Olympics.

And yet, that is exactly what happened. On 23 July, three days before her first event, Novák escaped from the part of the Olympic village reserved for competitors from the Eastern Bloc. Her pants got caught in the barbed wire fence, but she was not injured. Gerard was waiting for her in a car next to the village, but she didn’t sit next to him. Instead, as a precaution, she lay down in the back seat, where they covered her with a blanket. They didn't want to run into a roadside checkpoint because that would have wasted valuable time.

They didn't stop until they reached the Belgian embassy, where they exchanged vows in front of the ambassador. The ambassador was authorised to marry them, but as he had an official engagement at four o'clock that afternoon, they had to hurry. Novák also had to return to the village so that the communist officials travelling with the athletes would not suspect anything, so the ceremony had to be short. They did look for her, but her teammates somehow managed to explain her absence. They kept the marriage a secret for the time being, even Éva's sister, Ilona, who was also an Olympian, had no idea about it.

A few days later, on 26 July, Novák already competed as a married woman. She swam the best time in the preliminaries of the 200-meter breaststroke, and since she spoke English, she was happy to give interviews. The officials were so unaware of anything going on, that one of them even introduced Novák to a Belgian journalist waiting for an interview by the poolside. You may have guessed it: it was Pierre Gerard. They had no choice but to pretend that there was nothing between them and kept with the formalities.

The final of the 200-meter breaststroke was held on 29 July, and Éva Székely, who swam the entire race using the butterfly stroke (which was not yet banned for this event at the time), beat Novák, who ended up with the silver medal. On 1 August, Novák competed as one of the members of the 4×100-meter freestyle relay team. She was the third swimmer on the team after her sister. The team consisting of Ilona Novák, Judit Temes, Éva Novák, and Kató Szőke set a magnificent world record (4:24.4), finishing more than four seconds ahead of the Dutch, who finished with a time of 4:29, with the United States coming in third. This success was met with huge acclaim and recognition around the world, as it is not easy to find four competitors of such quality in a small country. (Hungary has not won a medal in this discipline since then.)

"I was a little worried in the morning that I would be exhausted in the afternoon after the preliminary round. But I was in such a good physical and emotional state that I didn't feel tired at all,"

said Novák, who swam the fastest time among the four Hungarians, completing the 100 meters in 1:05.1. Knowing that she had just gotten secretly married makes reading her second sentence again all the more interesting.

Her competition schedule was not over yet, because a day later she won another silver medal in the 400-meter freestyle final, finishing behind another Hungarian, Valéria Gyenge. This means that she won a total of three medals at these Olympic Games.

It is difficult to determine exactly when Novák revealed to the team leaders that she had married the Belgian journalist. What is certain, however, is that they allowed Gerard to board the plane that carried the best members of the delegation to Prague with Novák, from where they traveled to Budapest by train. Ten thousand cheering fans welcomed them at Keleti railway station. With 16 gold medals, Hungary achieved its best Olympic performance ever in Helsinki, finishing third behind the United States and the Soviet Union. (This was the first time the Soviets had participated in the Olympics.)

Of course, the successful athletes were also received by Mátyás Rákosi, the country’s communist leader at the time. Novák told him that her happiness was doubled because, in addition to her gold medal, she had also received a gold ring and got married in Helsinki.

The newlyweds were permitted to go on their honeymoon to Lake Balaton, only for the Hungarian authorities to expel Gerard from the country a few weeks later.

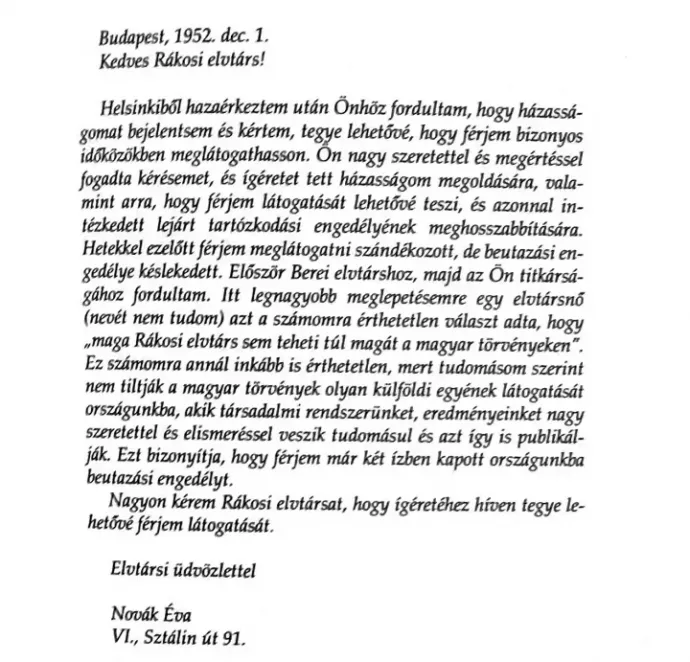

As Novák's passport was revoked at the same time, she was unable to go after him, so the Iron Curtain separated them. Novák made every effort possible to see her beloved, and on 1 December, 1952, she wrote a letter to Mátyás Rákosi. In it, she complained that her husband had not received permission to enter the country, so he was unable to visit her.

"First I turned to Comrade Berei, then to your office. To my great surprise, a female comrade (I don't know her name) responded with an answer that I found incomprehensible: 'Even Comrade Rákosi himself cannot override the law"', she said. This is all the more difficult to understand because, to my knowledge, Hungarian law does not prohibit individuals who view our social system and achievements with great affection and appreciation from visiting our country..."

The original letter from the champion's estate was later donated by Novák's granddaughter to the Olympic exhibition held at Budapest's Millenáris in 2021. We do not know whether Rákosi read it or wanted to read it, but we do know that nothing changed. Almost a whole year passed before a Hungarian delegation needed to travel to Belgium. The Belgian ambassador then decided that the Hungarians would only be allowed to enter the country on the condition that the Hungarian authorities also permitted Novák to travel. In December 1953, the Hungarians gave in to this subtle blackmail and Novák was allowed to go, so the couple could be reunited and they could begin their life together in Brussels.

Novák finished medical school in Belgium and continued her athletic career, competing for Belgium at the 1956 Olympics in Melbourne, but she did not make it to the finals. Two years later, she retired from swimming and opened an ophthalmology practice, becoming a renowned surgeon. In 1973, she and her sister were both inducted into the International Swimming Hall of Fame in the United States. The laudation highlighted that it is rare for someone to be able to perform at such a high level as she did in both breaststroke and freestyle. Novák later became the first woman to receive the French Order of Merit for Sport.

In 1972, a French television station chose their love story as the most beautiful romantic story of the 20th century, and they were given an hour-long TV special to mark the 20th anniversary of their marriage.

The commitment they made before the Helsinki Olympics proved to be lasting indeed, and Novák remained by her husband's side until his death. She gave birth to two daughters, Patricia and Pamela, who both spoke Hungarian, as do their children.

In 2002, Novák and her sister not only attended the celebrations marking the fiftieth anniversary of the Olympics in Finland, but also took a dip in the not-too-warm water of the swimming pool. They were joined by Kató Szőke, who had left the country in 1956 and was living in Los Angeles.

Éva Novák died in Brussels in 2005 at the age of 75, but in accordance with her last wishes, she was laid to rest in Budapest. Her sister lived until 2019.